Wage Theft, The $50 Billion Crime Against Workers

April 17, 2023

By Genevieve Carlton, Ph.D

In 2019, the total cost of every robbery in the country was $482 million.

The cost of wage theft was more than 100 times that number.

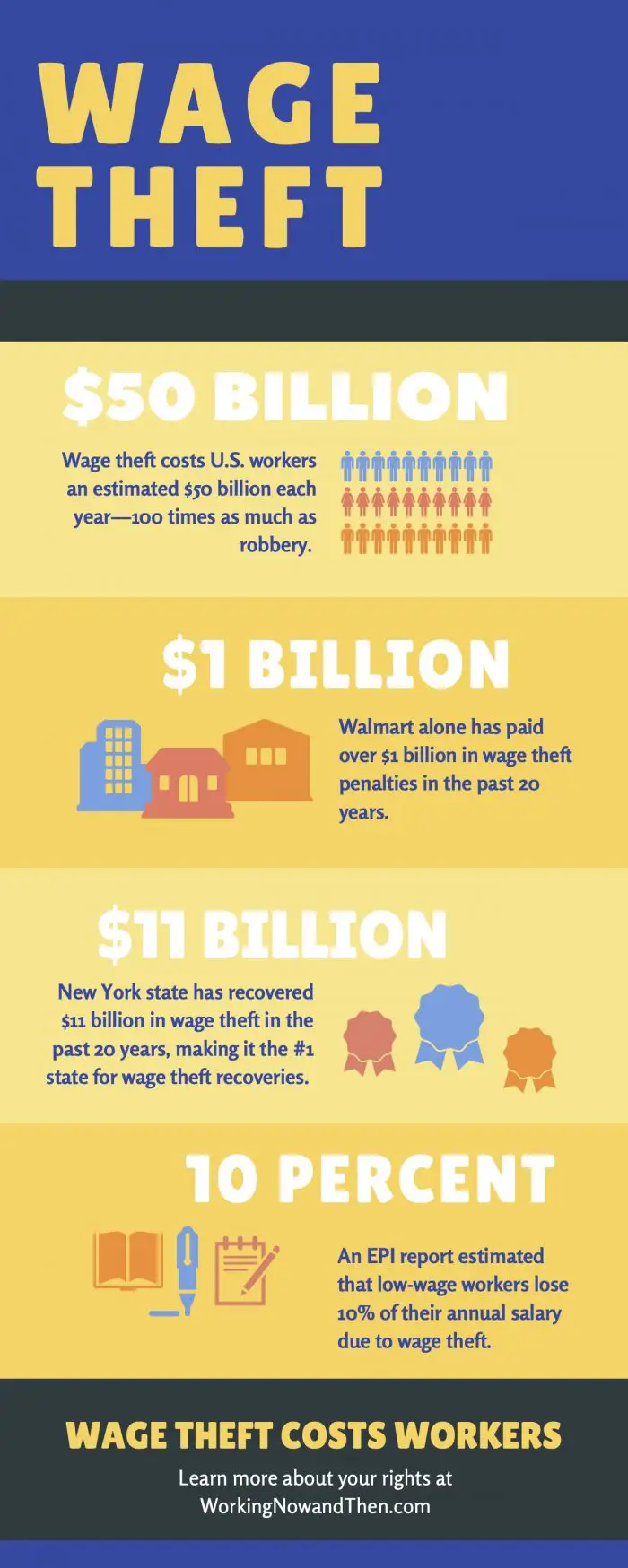

The FBI Uniform Crime Reporting program recorded 267,988 robberies in 2019. Those robberies cost businesses and the public $482 million in total losses. But wage theft costs workers $50 billion every year. And most of the time, employers get away with stealing money from their employees.

What is wage theft? Wage theft means underpaying workers. It can take several forms, including paying less than the minimum wage, withholding overtime pay, or not compensating workers for all of their work hours.

Imagine you work at a minimum wage job. But your company asks you to show up 30 minutes before the store opens every morning to prep – without paying you for that time. Over the course of a year, you’ve logged more than 100 unpaid hours of work. That’s wage theft.

Or let’s say you make $15 an hour as a stocker in a warehouse. During busy seasons, you put in overtime hours – but your employer doesn’t pay you the $22.50 per hour rate guaranteed by the law. You’ve lost out on hundreds of dollars of pay. That’s wage theft.

Wage theft isn’t just a problem in small companies. It’s also a major issue at some of the largest corporations in the country.

Walmart, Bank of America, FedEx, and Wells Fargo have something in common. They’ve all paid more than $200 million in wage theft penalties.

The overwhelming majority of companies fined for wage theft are large corporations, including many Fortune 500 companies. In its 2018 report, Good Jobs First cataloged the companies with over $1 million in wage theft penalties. The list reaches nearly 500 companies long––and the wage theft statistics add up to over $9 billion in stolen wages.

And when major corporations commit wage theft, it’s often more subtle than simply withholding pay. Instead, these corporations classify their workers as independent contractors instead of employers. That alone can save companies tens of thousands per worker in wages and benefits––all while costing each worker tens of thousands in lost wages.

Requiring off-the-clock work is another common form of corporate wage theft. For example, employers cannot require workers to perform job tasks during unpaid meal breaks. They also cannot ask workers to perform unpaid work before or after they clock out.

Some states stand out in the battle against wage theft.

When it comes to battling wage theft, one state stands out above the rest. New York has secured more than $11 billion in wage theft recoveries between 2000-2020. In cases against financial institutions and international banks, New York’s Department of Financial Services has secured major settlements for workers, according to research by Good Jobs First.

The $11 billion recovered by New York state does not include the many lawsuits filed directly by victims of wage theft.

Only four other states have recovered more than $100 million in wage theft cases. California posted around $1 billion in wage theft cases over a two-decade period, while Arizona reported $665 million, Texas recovered $632 million, and New Jersey secured $339 million.

At the federal level, the Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division recovers back pay for victims of wage theft. WHD reported record numbers for 2019, recovering $322 million for employees. That averages out to more than $1,000 per employee owed wages by their employer. Between 2014-2019, WHD recovered over $1.4 billion in wage theft actions.

Yet there’s still a massive gap between the wage theft recoveries reported by government agencies and estimates for how much employers underpay their employees. According to a 2014 report from the Economic Policy Institute, the true cost of wage theft is more like $50 billion a year.

Private lawsuits make up part of the difference. But most victims of wage theft never receive the money they earned.

The true cost of wage theft is even higher than $50 billion.

Wage theft is about more than lost wages – it’s about the cost to society when employers don’t pay their workers.

“Wage theft affects far more people than more well-known crimes such as bank robberies, convenience store robberies, street and highway robberies, and gas station robberies combined,” says Economic Policy Institute Vice President Ross Eisenbrey.

For those workers, especially those living paycheck-to-paycheck, even losing one hour of pay can make it hard to pay bills or buy groceries.

Consider the results from the EPI report, which investigated the wage theft statistics of low-wage workers in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Two in three workers experienced a pay-related violation every week.

“For low-wage workers, the wages lost from wage theft can total nearly 10% of their annual earnings,” says Eisenbrey.

Many of these workers struggle to save up to buy a reliable car or cover their rent––even though they’re working enough to afford these expenses. When employers underpay low-income employees, those workers suffer devastating consequences.

Fortunately, in addition to federal and state agencies prosecuting wage theft cases, victims of wage theft can also file a lawsuit.

Take the restaurant industry, for example. In 2016, McDonald’s paid $3.75 million in a wage theft settlement. The case accused the fast food corporation of not paying overtime and withholding pay for time spent cleaning uniforms. In 2012, Mario Batali settled a wage theft case for $5.25 million after making illegal deductions from the tip pool.

These wage theft examples reveal the power of workers coming together to protect their rights.

For more on wage theft, check out our piece on 11 common forms of wage theft or read our What is Wage Theft FAQ.

Working Now and Then was founded by Charles Joseph, who has over two decades of experience in employment law. He is the founding partner of Joseph and Kirschenbaum, a firm that has recovered over $140 million for clients.

Contact Working Now and Then to find out if you have a wage theft lawsuit.